Why talk

of a film made 60 years ago that was a super-flop?

Because

it would be trite to measure a world classic in terms of the revenue earned.

Kaagaz

Ke Phool (Paper Flowers) was released in August 1959. With all its flaws — and

they were many — it remains one of the most admired and discussed in Indian

cinema.

In

2002, Sight and Sound, the venerable magazine of the British Film Institute,

ranked Kaagaz… 160th among the greatest films ever made. Some others have

ranked it higher. In Bollywood, it turns up on all lists as one of the best

Hindi films of all time, among the top 10 if not the top five.

It was

removed after a week or two after its release in the few theatres it was shown.

Impatient viewers, the story goes, pelted the screen with stones in New Delhi’s

(now closed down) Regal theatre.

Yet,

it is talked about with the same enthusiasm as Mughal-e-Azam, made a year later,

the magnificent 16th century love story of Akbar the Great, his rebellious son

Salim and the latter’s love Anarkali, a court retainer.

As a

student, I repeated seeing ‘Kaagaz…’ within 24 hours, spending meagre pocket

money. I remember selling some old books and magazines to pay for a third

viewing.

Regarded

by many as India’s equivalent of Sunset Boulevard, Kaagaz… became a commercial

hit, not when released, not at home, but at its 1984 re-release in Germany,

France and Japan.

By

that time Guru Dutt, the protagonist and others who had put life into the

movie, had passed away. Waheeda Rehman, whom Dutt turns into a star but courts

controversy, is the only key player alive.

Dutt

acted, produced, wrote the story and directed it. It is a long flashback about

a famous film director, Suresh Sinha. He meets Shanti, played by Waheeda, on a

rainy night. By a stroke of creative inspiration, he makes her the heroine in

his next film. Shanti becomes a star.

Their

proximity causes gossip. Scandalised at school, Suresh’s daughter confronts

Shanti. Heartbroken, she abandons her career.

His

personal life is a mess since he married above his station. His wife and her

aristocratic family of British India’s civil service are contemptuous of his

profession.

Suresh

turns to alcohol, loses everything. “Self-respect is the only thing I am left

with,” he tells Shanti who entreats him to return to film-making. Suresh returns

to the grand studio, only to sit on the Director’s chair and die.

I

think the film was ahead of its time. Its theme was too radical for the Indian audiences

of the 1950s, used to simpler plots and storylines. The underlying tones of the

film were complex.

A wife

being the villain seemed unacceptable when ‘Kaagaz…’ was widely viewed as

autobiographical. Reel life and real life got mixed up in public mind. Dutt’s

real-life wife Geeta, a renowned singer and a picture of grace and beauty,

received much unsought-for sympathy.

It

was a technological landmark, the first to be shot in 70mm CinemaScope. But

that was also its undoing. India then had less than 10 theatres with wide

screen. With such constraints, commercial failure was foregone. Yet, it was

critically acclaimed and won several awards.

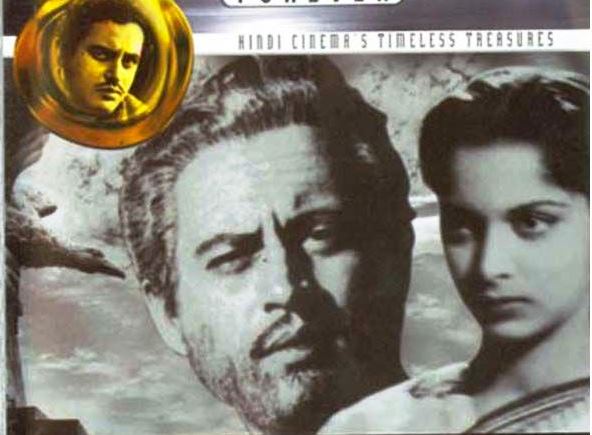

In

that era of black-and-white posters, it had the two lead actors together, with

a rose in red.

Ironically,

51 years after filming Kaagaz… in 2010, the long-forgotten Murthy, at 86, was honoured

with the Dadasaheb Phalke Award. This was after film analyst Gautam Kaul

projected him as a freedom fighter who had gone to jail before joining films. Murthy

remains the only ‘technical’ man to win a Phalke.

His black-and-white

photography wove Kaifi Azmi’s lyrics into sheer poetry. S D Burman’s music,

capturing the pathos, was sublime.

Many

I know came out of the theatre crying. Six decades on, the impact on one’s

sensitivities is the same. Songs “Bichhde

sabhi baari baari” and “Waqt ne diya”

are timeless.

In

the post-War II era of Indian cinema, when stars called the shots, Guru Dutt,

like Raj Kapoor, was an actor-director. Ironically, both Kapoor and Dutt, when

they made autobiographicals, failed to woo audiences. Kapoor’s Mera Naam Joker

and Dutt’s Kaagaz… were super-flops initially. Yet, they remain among the most

debated films.

Although

Hollywood’s impact was huge, Kaagaz… remains essentially Indian. It was unique in

an era when, to the world outside, Indian cinema was more about mythology, of

endless songs and dances and about social issues for which the West had neither

knowledge, nor patience to comprehend.

His

transparent concern about his creativity and his total honesty in narrating his

personal traumas make his films unique.

Alas,

Dutt’s master-touch was missing in its screenplay. Kaagaz… dragged. Late film

historian Firoze Rangoonwalla records: “It was shot very lovingly. But the

subject and its treatment made it a dismal failure.”

Dutt

was so shattered at the failure of his opus that he lost the appetite for

experimentation.

His

next film, Chaudahavin Ka Chand, was a love triangle in the north Indian Muslim

milieu, though alluring, was ‘safe’.

Distributors

who had lost money on ‘Kaagaz…” refused to release the new film unless Dutt

made advance payments. This hurt him.

A story

goes that when he was haggling with them, a telegram arrived from Los Angeles.

A copy of ‘Kaagaz’ had been taken to Hollywood by Dutt’s cinematographer V.K.

Murthy, who had earlier worked there and earned credits for, among other films,

Karl Foreman’s The Guns of Navarone.

Murthy

showed Kaagaz… to a select audience that included the legendary Cecil B.

DeMille, maker of The Ten Commandments.

On

receiving DeMille’s congratulatory telegram, Dutt, defying his financiers, sold

the film to a new set of distributors. It was a super-hit that made Dutt

solvent again. But he could not salvage Kaagaz.

Abrar

Alvi, who scripted both films, called Dutt “the Hamlet of Indian Cinema, a

restless man but genuine and sincere to the core”.

Dutt

made outstanding films. But after Kaagaz, he did not take chances with

technology and themes and did not take the directorial credit.

He

died young, at 39, his many dreams unfulfilled, leaving behind the image of a

tormented soul, on and off the screen.

Kaagaz…

may not move the average present-day audiences used to fast-paced cinema with

loud music. But it would strike a chord among the discerning of all ages,

particularly the university-going young. It’s a cult film.

Dutt

remains an inspiration for many contemporary filmmakers who combine creativity

with commercialism and meet the demands of a busy, impatient and demanding

audience exposed to world cinema that flocks to the multiplex theatres.

They do make good films today. But minus Dutt’s passion and sensitivities, whether they can make another ‘Kaagaz…’ is doubtful.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com