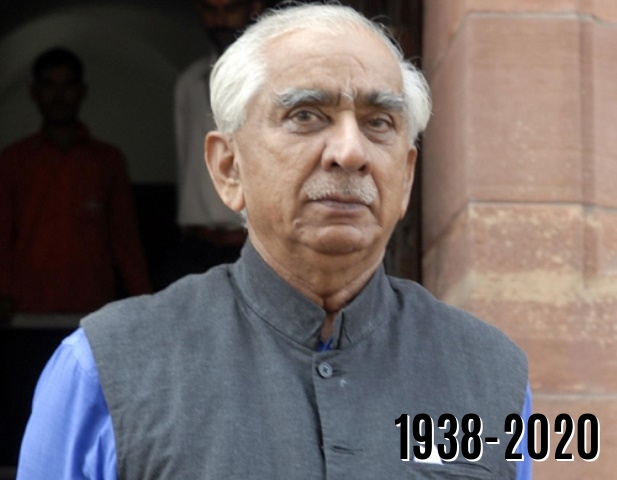

Last Sunday’s morning began on a note of grief and nostalgia for many an Indian at the passing away of Jaswant Singh, nine-term lawmaker, a perceptive and an efficient minister in the Atal Bihari Vajpayee Government and above all, a good man. All Members of Parliament are supposed to be, and are addressed as, ‘honourable’. Jaswant Singh was “a man of honour.”

That few visited him, or even inquired about him, during the six years he lay in coma after a fall in the bathroom in 2014, shows how cruel the world is, particularly if one is in public life and has fallen out of grace – no matter how graceful a person one has been. And Singh, even to his critics, was a man with old world grace and charm.

He had been expelled from the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) not once, but twice. The first time, because he displayed the courage of conviction of calling Pakistan’s founder, Mohammed Ali Jinnah ‘secular’. He had made the same ‘mistake’ as another veteran: L K Advani. The very idea is anathema to India’s Hindu ‘nationalists’ who believe in undivided India and blame the rival Congress Party, especially first Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, for having ‘conceded’ Pakistan. Ironically, Advani brought him back to the BJP.

It is another matter that Jinnah’s ‘secular’ approach while founding Pakistan, cited in his August 1, 1947 radio broadcast, is under scrutiny. Portrayed by Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal and held dear by liberals on both sides of the India-Pakistan divide, it has recently been challenged by another Pakistani scholar Ishtiaq Ahmed. So, there is no last word in history.

Although a BJP founder, Singh had been a misfit since he did not come from the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh (RSS) stable, as is largely the case with the Narendra Modi Government today. Along with Sushma Swaraj, who had socialist background, Singh had faced stiff resistance from the Sangh.

That he handled key portfolios of Defence, Finance and External Affairs despite these reservations is a tribute to both, Singh and Vajpayee, who also resisted pressures with regard to Brajesh Mishra, making the latter India’s first National Security Advisor.

Like it was when Swaraj and another stalwart, Arun Jaitley died within days last year, Singh’s death has triggered nostalgia for the good, not-so-old times at the turn of the century, when the government talked to the media. Today, it is selective with a few powerful and pliable, while the rest are talked at, or, in this era or tweets and social media, simply ignored.

A soldier who resigned his commission while just 27, Singh was erudite and knowledgeable. He never shed his army background, plus old feudal graces typical of Rajasthan, although he was no Maharajah.

He bore the odium, much longer and long before Shashi Tharoor, whose English speaking has these days impressed many – or has troubled many in the current ruling dispensation and some jealous fellow- Keralites. With his famous baritone, Singh spoke both English and Hindi in measured tones. He may have never shouted except when he was in the Army.

A Cavalry officer, his knowledge came in handy when the Bofors gun signed during the Rajiv Gandhi era became controversial. Perhaps the only lawmaker who understood the gun, he examined it and went on record, despite being in the opposition, to say that it was a good weapon system. Some others, reportedly, only felt the gun, and then resorted to the set party line to praise or pummel it.

ALSO READ: A Political Stalwart Of Vajpayee Era

As foreign minister, Singh firmly backed Vajpayee on the 1998 nuclear tests that brought India global sanctions. He then talked over two years with Strobe Talbott, then United States deputy secretary of state, and paved the way for President Bill Clinton’s India visit in 2000.

Ex-soldier Jaswant Singh and ex-journalist Talbott got on well. In his book ‘Engaging India: Diplomacy, Democracy & the Bomb’, Talbott describes how he and Jaswant Singh met 14 times in seven countries across three continents to lay the groundwork for a new understanding of India. That was the turning point in Indo-US relations, a process that continued under eight years each of George W. Bush Jr. and Barack Obama, not to speak of Donald Trump.

One blot on Singh’s otherwise good reputation and bright political career was escorting three Pakistani militants to Kandahar to rescue the Indian Airlines aircraft and passengers hijacked in 1999. Those were difficult days of public outpourings of panic and anger at the hijack, heightened by the television channels. Some relatives of the passengers stormed the venue of Singh’s press conference. India was at a low ebb.

There is little on record to show how Singh became a scapegoat in a panic-triggered government decision to free the militants as demanded by the Taliban, then ruling Afghanistan. Along with late George Fernandes, then Defence Minister, Singh was in an abject minority in the Cabinet meeting.

But he did the unenviable task of escorting the militants to Kandahar and endured the pain of having to talk to the Taliban, whom India did not recognise. “I had to bring all our citizens back home safely. If that involved talking to the Taliban, I didn’t mind.” He explained in his memoirs that he was executing a decision that was collective. The discipline of a soldier, perhaps?

Singh was a realist. Despite his Rajput roots, he was willing to talk to Pakistan at Vajpayee’s historic Lahore visit. This signalled India’s (under a BJP premier) willingness to acknowledge the 1947 Partition and Pakistan. And even after the Kargil conflict, he played a key role at the Agra Summit that failed for lack of clear understanding and preparations.

The party hardliners did not forgive Singh’s liberal ways. Even on domestic issues, Singh was an able trouble-shooter whom Vajpayee called his ‘Hanuman’. Like Vajpayee, he was not into Ram temple dispute. After the damage was done, he was encouraged to conduct a conciliatory dialogue with the Muslim community. Vajpayee was, perhaps, nudging his party towards a broader, if not exactly secular, spread. But that was not to be. He lost power in 2004 and retired from public life.

All this seems unthinkable, a far cry today. Ram temple is becoming a reality and so is a mosque a distance away. India’s relations with Pakistan and China are bad and could get worse.

Over 15 years hence, these are but nuggets of nostalgia to cherish.

The writer can be reached at mahendraved07@gmail.com