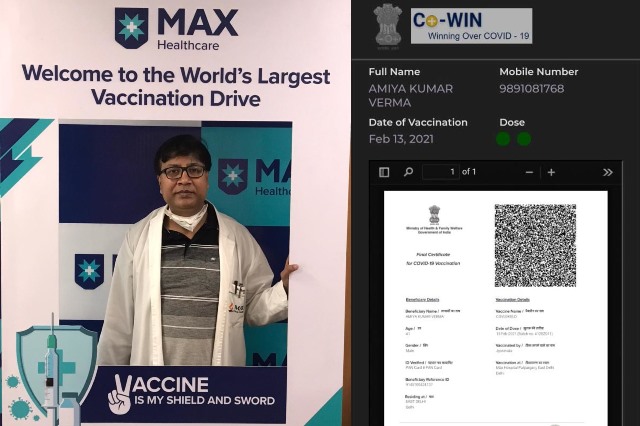

In a late night address to the nation on Saturday, December 25, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India would be administering third shots of vaccination (booster jabs) for those above 60 with co-morbidities as well as for frontline healthcare workers. He also announced that children aged 15-18 would also be eligible for COVID vaccines. These are timely decisions given that COVID’s latest mutant, Omicron, could spread rapidly in India. The challenge of vaccinating a population as large as India’s is daunting but the good news is that, at least according to official reckoning, 75% of adults have received the second dose of the vaccine.

That’s the good news. The not so good news is that if you take the entire population of the country, then just a little over 41% are fully vaccinated. Also, it may be a fact that the renewed surge of the virus may be inevitable. According to official estimates, at the time of writing, there have been around 422 reported cases of people infected by COVID. The actual figures in a country as large and as divided by inequality, accessibility, and lack of testing facilities could be way higher. The earlier waves of COVID’s spread were marked by a pattern: initial detection rates were slow, leading to complacency; and then, like a sudden horrific storm, the country was gasping for oxygen and hospital beds.

From most reports based on, albeit limited, research into the Omicron virus it seems that the latest mutant of the pernicious pandemic virus is milder, particularly when it affects fully or partially vaccinated people. However, these are not conclusive findings because the Omicron variant was detected very recently. What is known and is of concern is that this variant is more contagious and spreads much faster than earlier variants.

The other area of worry is the experience of other countries where Omicron is spreading. In Europe, UK, and the US, it is seen that the virus is affecting younger people (aged below 30) more than it is the older population. While there is little research yet to establish reasons behind this phenomenon, the fact is that India’s youth (18-20 year olds) account for more than 20% or more than 260 million people (that is more than half of the total population of the EU region of 447. million). Also, a large proportion of the Indian youth is not vaccinated yet. In that context, Prime Minister Modi’s announcement of vaccination for 15-18 year olds is in the right direction.

There is, however, another area of concern. Many countries in Europe have already slammed the emergency brakes in the form of new restrictions on public events, commuting, entertainment venues, and so on. Many states in India have also taken similar action. But when it comes to compliance by the Indian public, it is a different matter. The correct use of masks is nowhere near universal in India’s densely populated cities; and bans on congregations and public events are still flouted routinely. These can have alarming consequences.

When the second wave hit India, the anguish that millions suffered was heart-wrenching. A total of 48,000 people are estimated to have died as a result of COVID in India. Many more have suffered or are still suffering long-term consequences of the virus. Public memory is short but this is a virus that we need to be prepared to grapple with for a long time. And, while the authorities can attempt to do their bit by ensuring vaccination for all and stipulation of restrictions, much of the onus is on us, the ordinary citizens of the country, to be sensible in the face of adversity.

Hatred Rears Its Ugly Head… Again

The perceptible change in Indian society–no matter which socio-economic echelon you look at–is the increasing insecurity, anxiety and existential angst that minority communities in India have been experiencing over the past decade. It is probably not a coincidence that such feelings have intensified after the Hindustva-espousing BJP-led government came to power at the Centre in 2014. This has manifested in several events: a spate of violence involving alleged cow slaughter; pre- and post-election rioting; and targeted discrimination against certain minority communities.

In mid-December, at a three-day convention of Hindu hardliners in the ancient city and religious pilgrimage destination of Haridwar, several speakers made speeches that were inflammatory and could spark or incite violence against minority communities. In some instances, what was said was in innuendoes. But in a few, there were undisguised call for violence and even genocide.

In a country where secularism and equality for all are principles enshrined in the Constitution, instances such as these coming nearly 75 years after Independence are abhorrent. More importantly, it is the response of the authorities that is of concern. Although there were many protests against the speeches and FIRs were filed, no one had been arrested at the time of writing, more than a week after the convention was held.

What is also of concern is the silence of those in power. Prime Minister Narendra Modi has yet to comment on or condemn the speeches. His colleague, home minister Amit Shah has also not responded. Hindus make up 79.8% of India’s population and Muslims account for 14.2%; Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains account for most of the remaining 6%. A surge of majoritarianism and hatred of the kind that is demonstrated by the Haridwar gathering is an ugly development in a democracy that prides itself on tolerance and equality. If, in the hour of need, people at the highest level of power choose to remain silent, does it not legitimise the hate?